Give millennials a break

Millennials have been hardest hit by cuts. Antony Bennison, CC BY-NC

Millennials have been hardest hit by cuts. Antony Bennison, CC BY-NC

Evangelos Kontopantelis, University of Manchester

Young people are poorer than older people. And it’s not simply because the old have worked all their lives and are enjoying the fruits of their labours in their sunset years.

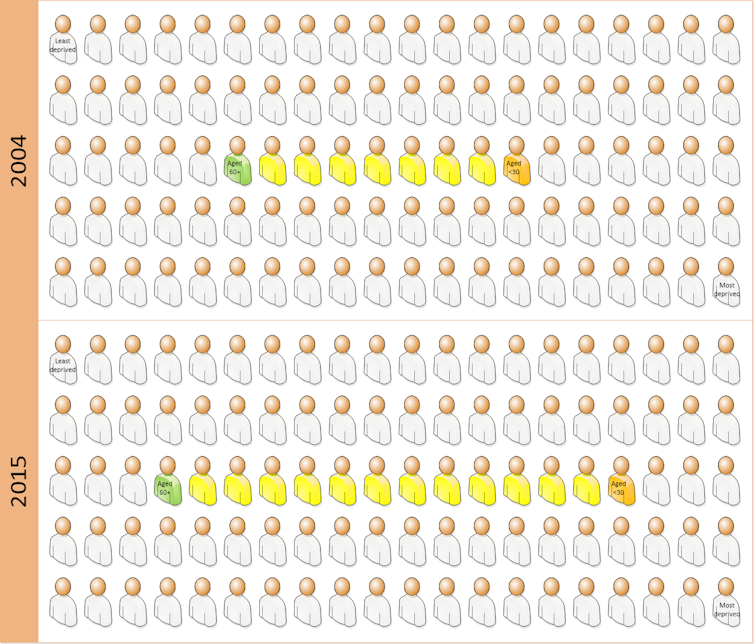

The wealth gap between the young and the old is on the rise in England. These were the stark findings of our research into deprivation levels between 2004 and 2015. We measured wealth (or lack thereof) using the the UK government’s English Index of Multiple Deprivation data, which pulls together relative deprivation across seven domains: income, employment, education and skills, health and disability, crime, barriers to housing and services, and living environment.

We found that relative deprivation (standard of living below levels enjoyed by the broader society, to a high enough extent to introduce hardship, with little or no access to resources) decreased for those aged 60 or over but increased for all other age groups. The under 30s endured most of the increase, including a worrying trend for infants aged 0-4. Perhaps surprisingly, relative deprivation also increased for those aged 30-59.

The increasing relative deprivation gap (in yellow) between the average person aged 60 or over (green) and the average person aged under 30 (orange), if the distribution of deprivation in England was depicted as 100 people arranged from least deprived (top left) to most deprived (bottom right)

The increasing relative deprivation gap (in yellow) between the average person aged 60 or over (green) and the average person aged under 30 (orange), if the distribution of deprivation in England was depicted as 100 people arranged from least deprived (top left) to most deprived (bottom right)

There are six main reasons for this trend.

1. The Great Recession of 2008

The recession that followed the 2007-08 financial crisis is the most well-known reason as to why the young are becoming poorer and poorer. The job market is not what it was before 2008 and austerity policies affected the “have-nots” the most. Because younger people usually fall into this category, they have been affected more than older generations.

2. Housing

The cost of housing has risen immensely in recent years, with the average house in England and Wales costing 7.6 times the average annual salary in 2016 – up from 3.6 times in 1997. Conventional wisdom says this is because there is a shortage of houses.

To some extent this is true, but property speculation is also at play. The housing market has been a self-reinforcing driver of wealth inequality.

Recent policies have aimed to drive down demand by discouraging the buy-to-let market. But large increases in house prices over a relatively short period of time have provided a large advantage to the older generation (for whom it was much cheaper to get on the property ladder, earlier).

3. Mechanisation of jobs

Machines, robots and engineering feats are leading to the disappearance of a large number of mid-level jobs in rich countries, and Britain is no exception. On the bright side, this has also led to an increase in demand for high-skilled jobs (like managers and scientists), but the number of these jobs is smaller to the number of mid-level jobs lost.

So the job market is rapidly becoming more and more imbalanced, with a large number of unskilled jobs available. These are the types of jobs that robots cannot yet perform, such as Amazon warehouse workers.

4. University tuition fees

For younger people to avoid a low-skilled and low-paid job, they need skills to successfully compete for the fewer jobs at the other end. This is where a university degree (or degrees) become essential. But, since 2006-07 in England, students have to pay for access to higher education. And the annual cost was up to £9,250 for EU students, with around 76% of all institutions charging the full amount in 2015-16.

5. Pensions

The black holes in pension schemes are much larger than it was thought. The young have to pay for these indirectly, since employers have to offer them worse employment terms to plug deficits in their ring-fenced pension schemes.

People currently at work not only have their salaries affected, but are also extremely unlikely to enjoy the same retirement benefits as their colleagues retiring before them – even when accounting for an increasing life expectancy.

6. The cost of raising a family

Younger people are more likely to care for young children and the average cost of raising a child to adulthood rose to a staggering £231,843 in 2016, up 65% from 2003.

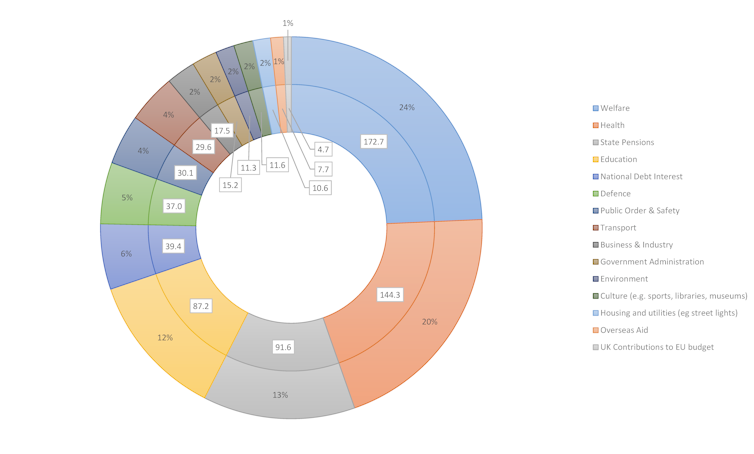

UK 2016-17 budget break down, billions of pounds (white) and percentages.

UK 2016-17 budget break down, billions of pounds (white) and percentages.

What does the future hold?

Things are likely to get worse with Brexit. Contribution to the EU is less than 1% of the government’s total budget (compare that to the cost of pensions, at 20% and rising). Interestingly, the EU is the biggest funder of social housing in Britain, and this of course will come to an end.

Baby boomers in their financial safety (triple locked pensions, properties that are owned outright) can afford to take a financial hit through Brexit. They are gambling with other people’s fortunes since they will be largely unaffected by a future economic crisis, unless pensions are slashed (the triple lock ensures that not even inflation can touch them).

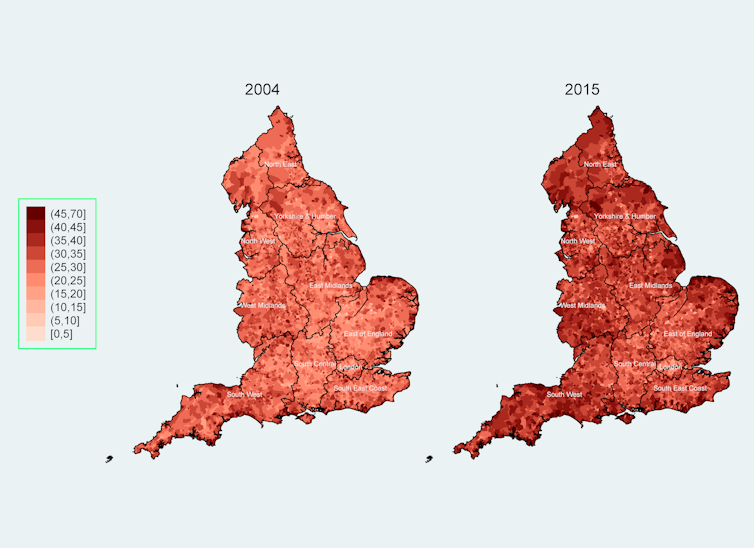

The percentage of people aged 60 or over in England is on the rise.

The percentage of people aged 60 or over in England is on the rise.

The primary challenge for young people born in Britain is not competing with young immigrants for jobs, but sustaining an older population that is increasing in size much faster than the young. This older population is also living longer and has poorer health, driving up healthcare spending, which is paid for by those in employment. Ironically, this is the generation that is now voting in a Conservative government that is stopping newer generations from enjoying the benefits that they had.

![]() So it’s no wonder that young people today are worse off than their parents’ generation. Not only should we give millennials a break, we should push for policies that will fix this gap, if we want to build a fairer society.

So it’s no wonder that young people today are worse off than their parents’ generation. Not only should we give millennials a break, we should push for policies that will fix this gap, if we want to build a fairer society.

Evangelos Kontopantelis, Professor in data science and health services research, University of Manchester

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.