Was Brexit really caused by austerity? Here's why we're not convinced

Like most bad dramas, keeping up with every development in the Brexit saga is difficult. Nevertheless you may have seen recent reports in the media, including in The Conversation, that “austerity caused Brexit”. But we doubt that a clear answer can come from a look at economics alone.

The idea that austerity swayed voters for Brexit is based on a paper by Thiemo Fetzer, an associate professor of economics at the University of Warwick. His paper claims to show that the welfare cuts under David Cameron’s coalition government of 2010-15 had a decisive impact on the UK’s decision to leave the EU. Fetzer argues that material economic changes encouraged grievances with the political system and that this led many to support first UKIP and then Brexit. By his calculations, austerity was responsible for as much as a ten percentage point swing in favour of Leave – thus tipping the outcome.

It’s easy to understand why these findings were so popular. For many, austerity confirms their suspicion that the government does not care about the poor and is willing to see them go to hell in a handcart, all for the promise of lower taxes. If austerity is also the cause of Brexit, these people see it as more evidence that their belief that the government doesn’t care is correct.

Election dissection

We are sceptical that austerity increased Leave’s vote by ten percentage points. Crucially, Fetzer mainly uses UKIP support in the years leading up to the 2016 referendum as a proxy for public support for leaving the EU. His ten-point claim comes from testing the effect of austerity on UKIP’s vote share in the local elections that took place each year since 2010.

But the study also includes estimates of the austerity effect on UKIP’s vote share at the 2014 European parliament elections and the general election of 2015. Importantly, these are much lower. Using the European elections, Fetzer finds that austerity boosted the Leave vote somewhere in the region of two to five percentage points. This could have been enough to change the outcome, given that Leave won by 3.8 percentage points. But this certainly makes it harder to claim that austerity had a decisive impact. The effect of austerity on UKIP support in the 2015 general election, meanwhile, is never explicitly stated in the paper. Yet it’s much closer to the European election swing than that of the local elections.

‘Aye aye, 'Kippers’ Gwyddion M. Williams, CC BY-SA

‘Aye aye, 'Kippers’ Gwyddion M. Williams, CC BY-SA

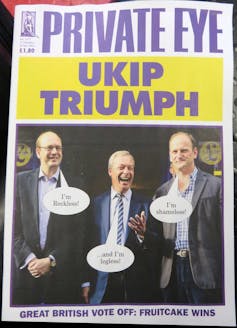

We are also unconvinced of UKIP’s rise from 2012 onwards. Fetzer argues that something must have changed in “left-behind” voters’ demand for a UKIP-like party, because UKIP itself did not change – and austerity fills this gap. Yet other political scientists have shown that UKIP did change after 2010. Previously, the party had targeted educated, middle-class Conservatives. It now shifted its attention to less educated, worse off, insecure and pessimistic (white) voters.

UKIP also made great efforts to campaign where these people lived, bringing the message to their doorsteps. And it benefited from a new-found media hype, which boosted party support. We suspect that UKIP-friendly voters had been there all along, that it was only supply and not demand that changed. And if austerity was not the cause of UKIP success with these voters, then the evidence that it caused the Leave vote is much weaker.

Elsewhere in his paper, Fetzer does go beyond using UKIP as a proxy for Brexit sentiment and looks directly at what was happening to support for leaving the EU in opinion polls. Here, he found that people affected by the welfare cuts were seven percentage points more likely to favour Brexit. This was only around 10% of the population, however – most people were affected by the cuts more indirectly. To make a proper case for the link between Brexit and austerity, you would have had to look at voter preferences more broadly.

The how and why

It will nonetheless seem intuitive to many that a pivotal policy like austerity could have left a Brexit-sized impression on British politics. Yet studies of austerity are novel at this point, and there is a lot we don’t know. And while various studies suggest voter choices are affected by the state of the economy, the political science literature gives reason to doubt that this happens consistently – even in response to the most obvious and highly publicised economic facts.

When voters do respond, they don’t all agree on who to hold responsible. Take the large majority who weren’t directly affected by austerity, for example: did they know that their area was hit by government tax credit freezes and bedroom taxes, for example – or were they more likely to notice municipal issues, like pot holes and fortnightly bins?

We also take issue with a described chain of events, of austerity causing Brexit by driving discontent with established politics. Again, political science research suggests it may not be so simple. Yes, parties and politicians follow the views of their supporters, but they shape them, too. Much of former UKIP leader Nigel Farage’s rhetoric has focused on corrupt elites, limited power and the UK’s lack of true democracy. It is hardly a surprise if the confidence of his supporters in the political system is diminished as a result. If Fetzer has the link the wrong way around, austerity’s effect on discontent would have been much less relevant to the vote.

To be clear, there’s no doubt Fetzer’s analysis is a good one. It will serve as inspiration for many to come. But most of the issues we have raised arise because he has taken an economist’s eye view of an issue that cannot be reduced to economics alone.

Whether by neglecting UKIP’s ability to adjust its messaging to appeal to different voters or underplaying other possible effects such as identity and values, the prescription is clear: a heavy dose of political science. It remains a possibility that austerity caused Brexit, but that’s unlikely to be the whole story.![]()

Lawrence McKay, Doctoral Researcher, University of Manchester and Jack Bailey, Doctoral Researcher, University of Manchester

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.