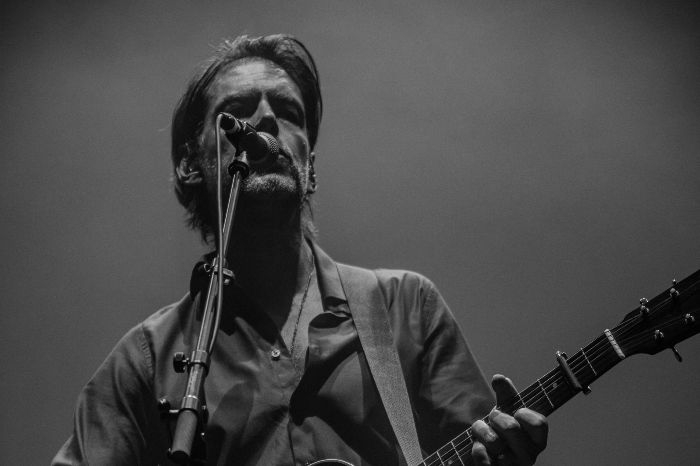

Winners of four Ivor Novello Awards, three Grammys and the joint most-nominated act in Mercury Prize history, Radiohead remain among the most revered bands in the music industry. But according to Ed O’Brien (BA Econ 1990), the band’s guitarist and co-songwriter, these accolades mean little compared to the recognition he received from our university in 2024.

To mark our 200th year, a stone engraved with Ed’s name was laid on Bicentenary Way – an installation celebrating key people and groups who have made an inspirational contribution to our institution and society throughout time.

“I think [music awards] are strange. The idea of comparing music and musicians with each other – I just don’t get it. Winners and losers? I’ve never understood it,” Ed says.

“But I think the University is amazing. I really loved my time at Manchester. So for them to honour what I’ve done since is definitely the most chuffed I’ve been.”

We all drew upon our experiences at university and brought them back to the band. And by the time we decided to really commit, we’d got a lot of our partying out of our system.

A Manchester love

Speaking to us from his home in the Welsh hills, Ed remembers exactly why he chose to study at Manchester: “I chose the University because of the city. And I chose the city because it was all about the music.”

Hailing from the outskirts of Oxford, Ed recounts how “distinctly un-rock’n’roll” his hometown was: “It was very traditional, so my whole pursuit was trying to get to a great music city.”

His obsession with the Manchester music scene and love for bands including The Smiths, Joy Division and New Order, along with the influence of Factory Records, brought him to the city in the late 1980s. But it was the people who made him truly fall in love.

Arriving at Owens Park Tower halls, Ed admits that he was “a little bit sniffy” about Fresher’s week at first: “I was trying to play it cool with bleach-white hair and all-black Dr. Martens,” he says, remembering his decision to dodge the traditional student social activities in favour of visiting a famous alternative emporium and sampling a northern delicacy.

“First I go to Afflecks Palace, and then I go and have my first chips and gravy. I loved it, and the woman who served me said ‘Do you want gravy on that, love?’ I’d never been called ‘love’. We didn’t have that down south.

“I felt this warmth. I was in the perfect city for me.”

Rockstar economics

Despite being offered a record deal while still at Abingdon School in Oxfordshire, Ed and his bandmates (Thom Yorke, Philip Selway, and Jonny and Colin Greenwood) were always going to go to university: “If you didn’t go on to further education after our school, it was a bit weird,” he says. “And I guess it was a sense of payback to your parents for putting you through this school."

But it would be his choice of degree that came as a surprise to some. “Thom’s gone to art college, Philip’s done Drama, Colin’s at Cambridge. And I did Economics. They’re like ‘What musician does Economics?’” he laughs.

In spite of this he always knew it was the right choice: “I wanted to understand how the world works. If you want to understand the world, you have to understand politics and economics.

“Now, more than ever, I still apply one of the first things my politics tutor said to us: ‘When you read something, whatever paper it is, you have to understand where they’re coming from and what’s their editorial slant’.

“That has stood me in such good stead. I am vociferous about reading source material and not relying on editorials – from the Left or the Right – because they all have their agendas.”

Ed credits his and his bandmates’ time at university with helping Radiohead become a success.

“It stood us in such good stead. We all drew upon our experiences at university and brought them back to the band. And by the time we decided to really commit, we’d got a lot of our partying out of our system.

“We’d had three or four years at university where those excesses had been indulged.”

An industry initiation

Ed’s time at Manchester also saw him become Social Secretary at Owens Park, working alongside the likes of Rob Ballantine (BA Econ 1983) – now Director at SJM Concerts – booking bands to play at the halls.

“I was cutting my teeth talking to agents. I tried to get Peter Hook from New Order to come and DJ at Owens Park. I rang up Factory Records and Rob Gretton – New Order’s manager – picks up the phone. He couldn’t have been nicer. And we ended up chatting for about 40 minutes.

“This was how I learnt about the music industry,” Ed says. “I knew that we had to take the business side seriously.”

The Manchester influence also made its way back to Ed’s hometown: “In ’89 I borrowed the PA from Owens Park. I brought a transit van up from Oxford for the summer holiday. I said I was going to get the PA ‘serviced’.”

With Thom Yorke as roadie, Ed hired a room above a pub and flyered across Oxford for their club night – an event that sold out for ten weeks in a row.

“I’d been part of this system in Manchester where you go out at night with a bucket of adhesive and you put up your posters. No one had really done that in Oxford before.

“I remember with the Haçienda, you got a flyer and it was beautiful because it was designed by Peter Saville, and you put it on your wall.

“We brought a lot of that to the band – the design and how you present yourself. That was really, really important.”

Becoming Radiohead

After leaving university, Ed, Thom, Colin, Jonny and Philip became known as Radiohead and signed their first record deal with EMI in 1991. They released early single Creep, which went on to become a worldwide hit, before their second album – 1995’s The Bends – and a support slot on tour with REM cemented their reputation as one of the UK’s most exciting alternative rock bands.

1997’s OK Computer catapulted the band to international stardom, including a legendary slot at Glastonbury Festival, and gave them the freedom to experiment with music styles – dipping into jazz, classical and electronica for albums Kid A and Amnesiac. A decade on, In Rainbows broke boundaries with its ‘pay what you want’ release. The band continued to play to millions across the globe for another ten years before deciding to pursue their own solo projects, like Ed’s first solo album, Earth, released in 2020.

Radiohead in 1992

Back up north

Ed has returned to Manchester several times over the years but one of the most memorable was his first visit after the release of Creep.

“We came back for an EMI conference [in summer 1992] in the Students’ Union Building. We played in the main hall [now Academy 2] which held about 800 people.

“To be playing in your old students’ union where I’d seen some amazing gigs – it was weird,” Ed remembers, after nights as a student watching John Martyn, Martin Stephenson and the Daintees, and an early Steve Coogan stand-up set at the same venue. “But I was suddenly back with my little gang – so I felt good about it.”

Their last group visit was in 2017 when the band’s two sell-out shows at Manchester Arena were moved to a single date at Old Trafford cricket ground following the Manchester Arena bombing two months earlier.

“There was a sense of occasion there, which you could feel,” reflects Ed.

I can’t remember who said that ‘Any revolution I’m a part of, I need to be able to dance in it’, but I agree with that wholeheartedly.

Music and activism hand-in-hand

As our conversation turns to the bigger concerts Radiohead have performed over the years, Ed acknowledges that performing in front of millions of fans around the world has a huge impact on the planet.

He’s just returned from a visit to Brazil with In Place of War – a charity set up by the University two decades ago that uses artistic creativity as a tool for positive change in places impacted by conflict and climate change. There he sat on a panel about sustainability in the music industry, and spent time with climate scientists and Amazonian tribal elders, immersing himself in an activism approach driven by positivity not anger.

“What I love about Brazil is that activism is done with a big heart and a smile. I actually think it’s more effective in how you win people over, rather than defining everything by us and them.

"I can’t remember who said that ‘any revolution I’m a part of, I need to be able to dance in it’, but I agree with that wholeheartedly,” he says.

Back in 2006, conscious of the impact they were having on the planet, Radiohead commissioned a report to assess the ecological footprint of their North American tours. Despite the band’s refusal to fly by private jet, Ed thought that it would be their travel that had the biggest impact, but the results revealed otherwise.

“The audit came back and said the band is responsible for 15% of the carbon footprint. The truth is that the biggest carbon footprint comes from the audience.

“Previous to the report, we’d avoided playing arenas. We tried to find beautiful places. And then we realised that it was the places with good infrastructure and public transport that were better for the planet.”

The findings are backed up by research from the University’s Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research, whose Super-Low Carbon Live Music roadmap successfully guided trip-hop collective Massive Attack in staging a one-day festival in Bristol – breaking the record for the lowest-ever carbon emissions from a show of its kind. The post-festival report concluded that the provision of extra public transport after the show played the biggest part in reducing its climate footprint.

“If you were going to be ideological about it, you could argue that we shouldn’t tour – because it’s not the responsible thing to do,” Ed says. “But what you’re doing is bringing love and light into people’s lives. You help them forget some of the troubles they might be carrying. You help them feel less alone. And I think at the moment, that’s a really important thing to be doing.”

Ed O'Brien

Standing up for what's right

Music as a force for good and protecting the artists who make it is also at the forefront of Ed’s mind.

“As a country, we punch above our weight culturally in all aspects – whether it’s music, literature, film, or arts. We always have done, and we should be looking after our artists,” he says.

Following the UK government’s decision to allow artificial intelligence (AI) companies to use copyright-protected work without the artist’s permission, Ed reflects on the threat of such technology.

“You don’t have to be a rocket scientist or a fortune teller to see what’s going to happen. And I just find it unbelievable. Once again, particularly in popular music, musicians and what we do for the economy gets taken for granted.”

In February 2025, Ed was credited as a co-writer of Is This What We Want? – a 47-minute-long album of complete silence recorded in studios and performance spaces in protest of the plans.

Its 12 track titles form the sentence ‘The British government must not legalise music theft to benefit AI companies’.

A forever connection

It’s this passion for doing the right thing, as well as his music, that earned Ed his place on Bicentenary Way. In summer 2024, while visiting the University with In Place of War for a panel discussion on creative activism, Ed saw his stone for the first time.

“For me, it really means something,” he says.

“[Musician and journalist] John Robb said to me that the University is key to the dynamic force of Manchester. He said all those people come in with outside influences and they throw themselves into the Manchester melting pot, and when they leave, they take Manchester with them.”

There are few better examples than Ed.

Find out more about In Place of War.