The Beyer Building

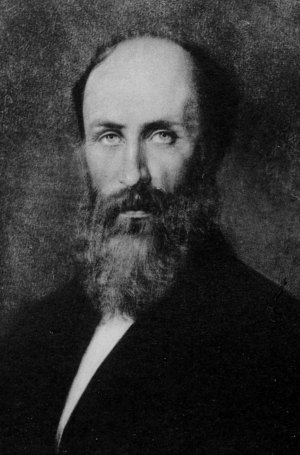

The Beyer Building opened in 1887 to house geology, zoology and botany. It was named for Charles Beyer (1813–1876), a German-born engineer and a major donor to Owens College.

Charles Beyer was an accomplished engineer, known worldwide for Beyer-Peacock railway locomotives. Like other German engineers and industrialists in Manchester he appreciated and supported scientific education in colleges – rather than simply relying on training by apprenticeship, which remained the usual British route.

Beyer was born in Saxony to a family of hand weavers. He was apprenticed as a boy to this un-remunerative trade but a doctor, who had chanced to see one of his drawings, persuaded his parents to send him to the polytechnic at Dresden. After four frugal years there he went to work in Chemnitz – here the local mill owners paid him to visit Britain to report on innovations in cotton spinning. Aged 21 he then moved to Manchester, initially working as low-paid draughtsman. He was soon assisting the principal partner Richard Roberts, an inventor of genius but with little mathematics or draughtsmanship.

After Roberts retired in 1843, Beyer was the company's chief engineer for ten years, after which he set up in partnership with Richard Peacock to specialise in locomotives. Their forge and factory in Gorton, east Manchester, supplied thousands of locomotives to railways across the globe until 1966. Beyer died in 1876 at his country home in Wales, leaving £100,000 to the College (about £8 million in today's money). The legacy helped fund the appointment of new professors and the provision of new buildings.

The Beyer Building was opened in 1887 to house geology, zoology and botany. It was connected to the Manchester Museum, opened the same year, which contained the specimens used in teaching and research.

From the founding of Owens College in 1851, natural history had been taught by William Crawford Williamson, who had been the first curator of the Natural History Society's museum in Manchester. His specialism was fossil plants for which he acquired a world reputation. At Owens he taught botany until his retirement in 1892, having successively handed over geology and zoology to younger teachers with more formal training.

Geology had been taken over in 1874 by William Boyd Dawkins. He had become fascinated by extinct mammals as a geology student in Oxford, and after graduation he worked on the Geological Survey with Thomas Henry Huxley. Like Williamson, Dawkins first came to Manchester as the curator of the museum, just before the collections moved to the new buildings of Owen College. He was largely responsible for the layout of the Manchester Museum when it opened in 1887. Widely known for studies on ancient hyenas, rhinoceroses and early man, Dawkins also consulted for a projected Channel tunnel in 1882 and helped discover the Kent coalfield.

Zoology was taught from 1879 by Arthur Milnes Marshall, who had studied biological sciences – especially embryology – at Cambridge. At Owens he worked on the development of the brain. A brilliant teacher and evening lecturer, he was also a keen mountaineer. Like a number of Victorian scientists he died young in a climbing accident.

Williamson's successor in botany, Frederick Ernest Weiss, came from Bradford but had been educated in Germany universities. He greatly expanded the department and served for a time as acting vice-chancellor. Like Williamson, he was interested in coal fossils. From 1904, Marie Stopes also worked here on palaeobotany – the first woman lecturer in the Faculty of Science. She later became famous for her book Married Love and her advocacy of birth control.